It’s been a little over eight years since we first started talking about Neural Processing Units (NPUs) inside our smartphones and the early prospects of on-device AI. Big points if you remember that the HUAWEI Mate 10’s Kirin 970 processor was the first, though similar ideas had been floating around, particularly in imaging, before then.

Of course, a lot has changed in the last eight years — Apple has finally embraced AI, albeit with mixed results, and Google has obviously leaned heavily into its Tensor Processor Unit for everything from imaging to on-device language translation. Ask any of the big tech companies, from Arm and Qualcomm to Apple and Samsung, and they’ll all tell you that AI is the future of smartphone hardware and software.

And yet the landscape for mobile AI still feels quite confined; we’re restricted to a small but growing pool of on-device AI features, curated mostly by Google, with very little in the way of a creative developer landscape, and NPUs are partly to blame — not because they’re ineffective, but because they’ve never been exposed as a real platform. Which begs the question, what exactly is this silicon sitting in our phones really good for?

What is an NPU anyway?

Robert Triggs / Android Authority

Before we can decisively answer whether phones really “need” an NPU, we should probably acquaint ourselves with what it actually does.

Just like your phone’s general-purpose CPU for running apps, GPU for rendering games, or its ISP dedicated to crunching image and video data, an NPU is a purpose-built processor for running AI workloads as quickly and efficiently as possible. Simple enough.

Specifically, an NPU is designed to handle smaller data sizes (such as tiny 4-bit and even 2-bit models), specific memory patterns, and highly parallel mathematical operations, such as fused multiply-add and fused multiply–accumulate.

Mobile NPUs have taken hold to run AI workloads that traditional processors struggle with.

Now, as I said back in 2017, you don’t strictly need an NPU to run machine learning workloads; lots of smaller algorithms can run on even a modest CPU, while the data centers powering various Large Language Models run on hardware that’s closer to an NVIDIA graphics card than the NPU in your phone.

However, a dedicated NPU can help you run models that your CPU or GPU can’t handle at pace, and it can often perform tasks more efficiently. What this heterogeneous approach to computing can cost in terms of complexity and silicon area, it can gain back in power and performance, which are obviously key for smartphones. No one wants their phone’s AI tools to eat up their battery.

Wait, but doesn’t AI also run on graphics cards?

Oliver Cragg / Android Authority

If you’ve been following the ongoing RAM price crisis, you’ll know that AI data centers and the demand for powerful AI and GPU accelerators, particularly those from NVIDIA, are driving the shortages.

What makes NVIDIA’s CUDA architecture so effective for AI workloads (as well as graphics) is that it’s massively parallelized, with tensor cores that handle highly fused multiply–accumulate (MMA) operations across a wide range of matrix and data formats, including the tiny bit-depths used for modern quantized models.

While modern mobile GPUs, like Arm’s Mali and Qualcomm’s Adreno lineup, can support 16-bit and increasingly 8-bit data types with highly parallel math, they don’t execute very small, heavily quantized models — such as INT4 or lower — with anywhere near the same efficiency. Likewise, despite supporting these formats on paper and offering substantial parallelism, they aren’t optimized for AI as a primary workload.

Mobile GPUs focus on efficiency; they’re far less powerful for AI than desktop rivals.

Unlike beefy desktop graphics chips, mobile GPU architectures are designed first and foremost for power efficiency, using concepts such as tile-based rendering pipelines and sliced execution units that aren’t entirely conducive to sustained, compute-intensive workloads. Mobile GPUs can definitely perform AI compute and are quite good in some situations, but for highly specialized operations, there are often more power-efficient options.

Software development is the other equally important half of the equation. NVIDIA’s CUDA exposes key architectural attributes to developers, allowing for deep, kernel-level optimizations when running AI workloads. Mobile platforms lack comparable low-level access for developers and device manufacturers, instead relying on higher-level and often vendor-specific abstractions such as Qualcomm’s Neural Processing SDK or Arm’s Compute Library.

This highlights a significant pain point for the mobile AI development environment. While desktop development has mostly settled on CUDA (though AMD’s ROCm is gaining traction), smartphones run a variety of NPU architectures. There’s Google’s proprietary Tensor, Snapdragon Hexagon, Apple’s Neural Engine, and more, each with its own capabilities and development platforms.

NPUs haven’t solved the platform problem

Taylor Kerns / Android Authority

Smartphone chipsets that boast NPU capabilities (which is essentially all of them) are built to solve one problem — supporting smaller data values, complex math, and challenging memory patterns in an efficient manner without having to retool GPU architectures. However, discrete NPUs introduce new challenges, especially when it comes to third-party development.

While APIs and SDKs are available for Apple, Snapdragon, and MediaTek chips, developers traditionally had to build and optimize their applications separately for each platform. Even Google doesn’t yet provide easy, general developer access for its AI showcase Pixels: the Tensor ML SDK remains in experimental access, with no guarantee of general release. Developers can experiment with higher-level Gemini Nano features via Google’s ML Kit, but that stops well short of true, low-level access to the underlying hardware.

Worse, Samsung withdrew support for its Neural SDK altogether, and Google’s more universal Android NNAPI has since been deprecated. The result is a labyrinth of specifications and abandoned APIs that make efficient third-party mobile AI development exceedingly difficult. Vendor-specific optimizations were never going to scale, leaving us stuck with cloud-based and in-house compact models controlled by a few major vendors, such as Google.

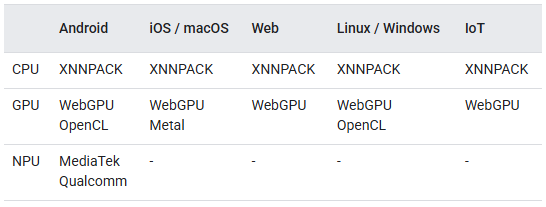

LiteRT runs on-device AI on Android, iOS, Web, IoT, and PC environments.

Thankfully, Google introduced LiteRT in 2024 — effectively repositioning TensorFlow Lite — as a single on-device runtime that supports CPU, GPU, and vendor NPUs (currently Qualcomm and MediaTek). It was specifically designed to maximize hardware acceleration at runtime, leaving the software to choose the most suitable method, addressing NNAPI’s biggest flaw. While NNAPI was intended to abstract away vendor-specific hardware, it ultimately standardized the interface rather than the behavior, leaving performance and reliability to vendor drivers — a gap LiteRT attempts to close by owning the runtime itself.

Interestingly, LiteRT is designed to run inference entirely on-device across Android, iOS, embedded systems, and even desktop-class environments, signaling Google’s ambition to make it a truly cross-platform runtime for compact models. Still, unlike desktop AI frameworks or diffusion pipelines that expose dozens of runtime tuning parameters, a TensorFlow Lite model represents a fully specified model, with precision, quantization, and execution constraints decided ahead of time so it can run predictably on constrained mobile hardware.

While abstracting away the vendor-NPU problem is a major perk of LiteRT, it’s still worth considering whether NPUs will remain as central as they once were in light of other modern developments.

For instance, Arm’s new SME2 external extension for its latest C1 series of CPUs provides up to 4x CPU-side AI acceleration for some workloads, with wide framework support and no need for dedicated SDKs. It’s also possible that mobile GPU architectures will shift to better support advanced machine learning workloads, possibly reducing the need for dedicated NPUs altogether. Samsung is reportedly exploring its own GPU architecture specifically to better leverage on-device AI, which could debut as early as the Galaxy S28 series. Likewise, Immagination’s E-series is specifically built for AI acceleration, debuting support for FP8 and INT8. Maybe Pixel will adopt this chip, eventually.

LiteRT complements these advancements, freeing developers to worry less about exactly how the hardware market shakes out. The advance of complex instruction support on CPUs can make them increasingly efficient tools for running machine learning workloads rather than a fallback. Meanwhile, GPUs with superior quantization support might eventually move to become the default accelerators instead of NPUs, and LiteRT can handle the transition. That makes LiteRT feel closer to the mobile-side equivalent of CUDA we’ve been missing — not because it exposes hardware, but because it finally abstracts it properly.

Dedicated mobile NPUs are unlikely to disappear but apps may finally start leveraging them.

Dedicated mobile NPUs are unlikely to disappear any time soon, but the NPU-centric, vendor-locked approach that defined the first wave of on-device AI clearly isn’t the endgame. For most third-party applications, CPUs and GPUs will continue to shoulder much of the practical workload, particularly as they gain more efficient support for modern machine learning operations. What matters more than any single block of silicon is the software layer that decides how — and if — that hardware is used.

If LiteRT succeeds, NPUs become accelerators rather than gatekeepers, and on-device mobile AI finally becomes something developers can target without betting on a specific chip vendor’s roadmap. With that in mind, there’s probably still some way to go before on-device AI has a vibrant ecosystem of third-party features to enjoy, but we are finally inching a little bit closer.

Thank you for being part of our community. Read our Comment Policy before posting.